A Brief History

The First Carols

On a trip from Rome in 1223, Francis of Assisi and his followers stopped at the small village of Grecia, near his birthplace. At the time, in some parts of the Christian Church, a system of beliefs, associated with the Paulician sect, had taken hold. While Paulicians believed the Gospel of Luke, and the letters of Paul, they did not believe that Jesus was indeed the son of Mary, because a good God could not have taken flesh and become man, who in their view, was fundamentally evil. Eager to combat this heresy and dramatize the Incarnation of God through the birth of Jesus Christ, St. Francis and his followers created what would become the first Nativity Scene, and sang hymns to the Lord Jesus [1]. As they sang songs (canticles) one of Francis’ followers had a vision of the saint (Francis) bending over a baby, laying in a trance, in the manger that he had constructed. As they sang the baby slowly awoke, symbolizing Christ bringing life to a dead and ‘wicked’ world [2]. The drama of that episode would later be captured in what later became known as the Christmas Mystery Play, and the songs that were sung are said to be the precursor of the Christmas Carol.

Mystery Plays dealt with religious subject matter, and were one of three dramatic forms (together with Morality Plays and Miracle Plays) performed outside of churches. The subject matter of Mystery Plays often centered on significant events depicted in the Bible, like the fall of Satan, the Birth of Jesus, or Judgement Day [3].

Carols came into prominence during the Middle Ages with the popularity of these plays. Mystery Plays could be quite lengthy, and performers serenaded audiences with carols during breaks in the performances [4]. By the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries carol singers and their music became so popular that they were incorporated into the play itself.

In time the Mystery Plays drifted away from their religious roots and fell out of favour with the religious authorities of the day [5]. They became more secular, and in some instances, even mocked religious figures like monks and priests. By the time of the Reformation and the Puritan Era, the public performance of Mystery Plays, effectively over.

Another era in the development of the Christmas Carol is the practice of wassailing. The Anglo-Saxon tradition of wassailing came into vogue during the Middle Ages [6]. At the beginning of each year, groups of merry-makers would go from house to house, wassail drink in hand, singing songs, wishing good cheer [7]. This practice would eventually evolve into caroling.

The golden age of carols was from the 1400s to the mid 17th century. However there seems to be an extended struggle between the performance of the Carol, with its origins in drama and later in dance music and its association with merry-making and drinking, and the emergence of Puritanism and the staunch Calvinist, Olive Cromwell–statesman, and lord protector of England, Scotland and Ireland [8]. In 1647 Cromwell and his Puritan Parliament abolished Christmas celebrations and other festivals altogether [9].

The Nineteenth Century

By the early 1800s Britain was in the middle of the Industrial Revolution. Inventions such as the spinning jenny and the power loom lead to the development of a textile industry. Innovations in the production of iron and steel led to the manufacture of products as diverse as appliances and tools, to ships and infrastructure [10]. The Revolution also gave rise to a manufacturing industry and a need for workers. Persons from the rural areas, particularly the young, migrated to the cities in search of work. With the migration to urban areas came the fear that rural traditions may be lost, a mere memory among the old who remained in the countryside. Among these traditions was the folk carol, and several prominent figures in music and literature set about to ensure this did not happen.

Mark Connelly, Professor of Modern British History at the University of Kent, in his book, Christmas, A History, chronicles the efforts of the men who collected and published the English folk carol, in so doing, preserving them for generations to come

He cites British MP Davies Gilbert as the first to systematically collect carols and render a basic description of the same, namely, music derived from folk songs, sung, not written, emanating from the south-western part of England, an area known as the West Country [11]. In 1822 Davies published A Collection of Ancient Christmas Carols, which included, ‘Whilst Shepherds Watched Their Flocks by Night’ and ‘The First Nowel That The Angel Did Say’ [12]. In 1833 William Sandys, a lawyer by profession, published Christmas Carols, Ancient and Modern, which included ‘God Rest You Merry, Gentlemen’; ‘Hark, the Herald Angels Sing’, ‘I Saw Three Ships’; and ‘The First Noel’ [13].

Another factor in the resurgence of the Christmas carol, Connelly argues, is the rise of Methodism. The Wesleys (John and Charles) used hymn singing as an integral part of their services, which were squarely directed at the common man and woman. Connelly suggests reaching back to the choral tradition of the carol and its folk song history was useful in relating to their followers [14].

The mid-nineteenth century saw the return of a choral tradition in the Anglican Church with the publication of Hymns Ancient and Modern [15]. A committee of clergymen, originally under the chairmanship of Sir. Henry Williams Baker, compiled and arranged the volume [16].

William Henry Monk, organist and director of music at King’s College, London, and ‘H. W. Baker, hymn writer, directed the compilation and arrangement of hymns [17].

The volume contained such Christmas favourites as ‘Oh Come, All Ye Faithful’, ‘Hark! The Herald Angels Sing’ and ‘While Shepherds Watch Their Flocks by Night.’

In 1853 Reverends J. M. Neale and T. Helmore published Carols for Christmas [18] but it was Christmas Carols New and Old, published in 1869 by Reverend H.R. Bramley ad Dr. John Stainer, that was the next significant development in the publication of Christmas carols, and was the ‘first large-scale circulation of a Christmas Carol collection [19].

In 1911 Cecil Sharpe, published English Folk Carols, a collection from southwest of England. [20]. Like many of his predecessors, Sharp’s rationale for compiling the collection was simply to preserve the history of the folk carol. Notable among English Folk Carols is ‘God Bless You, Merry Gentlemen’ and ‘I Saw Three Ships’ [21].

In 1919 Percy Dearmer, Canon of Westminster and professor of Ecclesiastical Art at King’s College London, and Martin Shaw, composer, arranger, educator, and T. S. Eliot collaborator, published The English Carol Book. The Great War had been fought, the Allies were victorious, and English ‘values’ (as opposed to British ones) had been protected, or so Connelly argues. The publication of Deamer’s and Shaw’s volume, with its affirmation of the ‘Englishness’ of the Christmas carol, fit neatly into this narrative [22]. The collection included ‘I Saw Three Ships’, ‘The First Nowell’, ‘Good King Wenceslas’, ‘What Child Is This’, among others. Dearmer and Shaw worked on several projects together with Ralph Vaughan Williams, including 1925s successful hymnal, Songs of Praise. However it was their 1928 volume that has become a classic, the definitive compilation of English Christmas carols, The Oxford Book of Carols.

In 1928 The Oxford Book of Carols was published. Edited by Dearmer, Shaw and Williams—composer and professor of music composition at Trinity College–it has been a commercial and critical success. At 480 pages it has undergone over forty editions, and currently contains 197 carols. It is known not only for its sheer breadth of songs but for its scholarly content as well. Dearmer’s preface has been specifically cited for documenting the source of the texts and the music, and in some cases, the history of the carols themselves [23].

Selected Carols

O Little Town of Bethlehem

Phillips Brooks was ordained in 1860 and would become one of the most prominent preachers of his era [24]. He became the Rector of Trinity Church in Boston in 1869 and Bishop of Massachusetts in 1891, a little more than a year before he died [25]. He was one of the clergymen to address the congregation at President Lincoln’s funeral in 1865.

Brooks believed in congregational hymn singing and wrote both Easter and Christmas carols [26]. He published the words to’ O Little Town of Bethlehem’ in 1891.

Ralph Vaughan Williams has been called one of England’s greatest composers. He together with Percy Dearmer is responsible for editing a number of significant books of praise. For his book, The English Hymnal, he matched the words of ‘O Little Town of Bethlehem’ to a tune he had first heard in the village of Forest Green [27].

Hark! The Herald Angels Sing

While many Christmas carols are like orphaned pieces of music—whose authors are not known, Hark! The Herald Angels Sing is not a member of this group, boasting a pedigree few carols can match. Charles Wesley, one of the best known and prolific hymn writers of all time–and with is brother, John—founded Methodism, wrote the words to this hymn, originally written as a poem. Charles Wesley has written close to 9,000 hymns [28] reportedly, ten times more than that other giant of hymn writing, Isaac Watts.

The original version of the poem was published in a collection of hymns in 1739 [29]. Modifications were made in subsequent years. Among those editing the piece was the famous evangelist and Wesley friend and colleague, George Whitefield [30].

Almost a hundred years later, in 1840, classical composer Felix Mendelssohn completed a cantata celebrating the 400th anniversary of Gutenberg’s invention of movable type [31]. Mendelssohn’s publisher had the cantata’s second movement translated into English.

William Hayman Cummings was an organist, a gifted tenor and admirer of Mendelssohn. As a boy he sang at St. Paul’s Cathedral, one of Mendelssohn’s favourite ‘haunts’. Cummings came across the second movement of Mendelssohn’s Cantata and realized that Charles Wesley’s Hark! The Herald Angels Sing fit the music. He transcribed the poem and music. He received so many requests for copies he took his arrangement to the publisher, Ewer and Co.—who happened to be Mendelssohn’s publisher as well. Cumming’s version was published it in1856, six years after Mendelssohn’s death [32].

Cummings marriage of Wesley’s and Mendelssohn’s work was included in the landmark publication, Hymns Ancient and Modern, in 1861 [33].

Silent Night

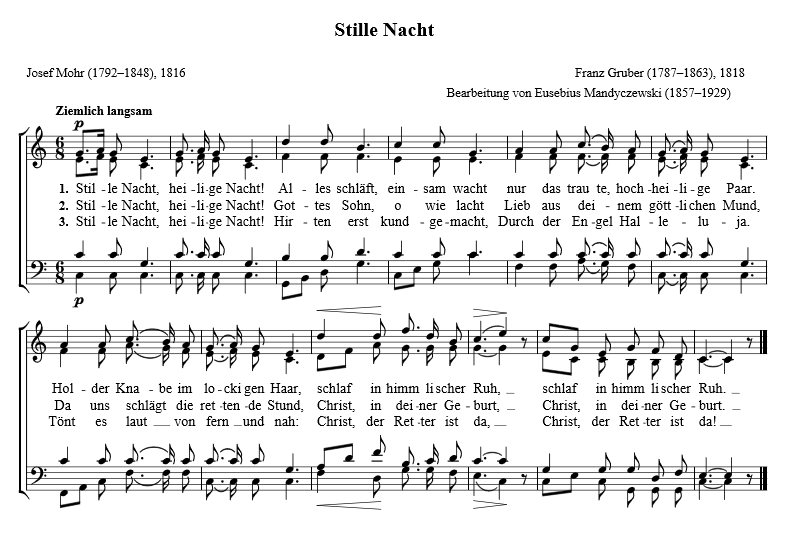

Silent Night was written in the village of Oberndorf, about 17 km north of the city of Salzburg in Austria [34]. According to an article in the Telegraph, Joseph Mohr, a Catholic priest, asked his friend and organist of his church to put music to a poem he had written a few years earlier called Stille Nacht. In a small Austrian village, on Christmas Eve, 1818, the two men sang Stille Nacht for the first time. In 1859, John Freeman, a priest at New York City’s Trinity Church, translated the hymn into English [35].

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Common, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=40855054

O Come, All Ye Faithful

The creators of some of our best known and most beloved carols are unknown. This is true for one of the most popular carols, ‘O Come All Ye Faithful.’ The words are from a Latin hymn (author unknown) entitled, Adeste Fideles.

John Francis Wade was the son of a cloth merchant based in Leeds, England. He was a devout Catholic who, in 1731 at age 20, fled the rising anti-Catholic sentiment of the early days of the Reformation, to an Abbey village outside of Paris. He became the monks’ musical scribe. He transcribed the Latin hymn, Adeste Fideles and to this day, he is credited by some as the author of the piece. It proved popular and in 1791 was published in a manual for teaching elements of music such as scales, intervals and clefs [36].

The music has been attributed to several individuals, among them King John IV of Portugal, the ‘Musician King.’ The author of the first English translation is not known definitively, but Francis Oakley persists as a possible candidate. Oakley was a member of the Oxford Movement and a canon at Westminster Abbey [37].

O Holy Night

Placide Cappeau was born in 1808 in the small town of Roquemaure on the banks of the Rhone in southern France. He wrote poetry, including an epic about his hometown, running to nine thousand verses [38].

In 1847 the cure (parish priest) of Roquemaure, asked Chapeau to write a piece for the church’s Christmas pageant. On December 3rd, the French poem that would become ‘O Holy Night’ was completed. Through a mutual friend, opera signer, Emily Laurey, Cappeau got his poem into the hands of Adolphe Adam, a leading opera composer of the day. Adam put the poem to music and on Christmas Eve, 1847, the soprano Emily Laure performed the song, now called Noel d’Adam, in public for the first-time [39].

John Sullivan Dwight was a Unitarian minister who trained at Harvard Divinity School [40]. He became involved in the transcendental movement and joined one of their communes as a music teacher [41]. He later became a music critic and founded a music publication, Dwight’s Journal of Music. In 1855 Dwight translated Cappeau’s Noel into English [42]. By 1860 Dwight’s version was published in France, England and the United States.

In 1906 the Canadian engineer, inventor, and former associate of Thomas Edison, Reginald Fessenden, successfully completed the first two-way radio communication between his home in Brant Rock, Massachusetts and Machrihanish, Scotland. On Christmas Eve of that year he made the first AM radio broadcast, which was heard as far away as Norfolk, Va. He played one of Handel’s compositions on a phonograph, read a Bible text and personally played ‘O Holy Night’ on the violin. In so doing Fessenden made the carol the first piece of music ever performed live on radio [43].

Final Thoughts

Christians have complained for years about the commercialization of Christmas, the secular nature of the holidays, a disregard for Jesus Christ, the person for whom the celebration is supposedly held. What may be surprising is that this is not necessarily anything new. There has always been a mixing of the secular and sacred around Christmas. And this misalignment of the Holiday and Jesus Christ applies to Christmas carols themselves. St. Francis of Assisi instigated the original carol to combat the heresy of the day, but his efforts were replaced by secular songs. Later, poems were written to celebrate the birth of the Christ child but much of the music that brought these words to life were not originally written to celebrate Jesus’ birth at all. Moreover many of the songs played at Christmas time in recent years have nothing at all to do with Jesus.

Nonetheless Christmas is not entirely lost for the Christian. The religious Christmas carol, and the people who wrote and preserved them, have ensured that the Holiday’s namesake is still welcomed at the party.

© 2018 Weldon Turner. All Rights Reserved.

Media

Amateur Waits24th December 1891: A country house party serenade their neighbours with Christmas carols on Christmas Eve.

Original Artwork: Drawn by Arthur Hopkins. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Details

Credit:Hulton Archive / Stringer

Editorial #:3095656

Collection:Hulton Archive

Date created:24 December, 1891

Licence type:Rights-managed

Release info:Not released. More information

Source:Hulton Archive

Barcode:JF1832

Object name:99t/18/huty/13418/02

Max file size:3839 x 2712 px (135.43 x 95.67 cm) – 72 dpi – 2.1 MB

https://www.gettyimages.ca/license/3095656

Stille Nacht

By Rettinghaus – Volksliederbuch für gemischten Chor, Leipzig 1915, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=40855054

References

[1] Percy Dearmer, R. Vaughan Williams, Martin Shaw, Oxford Book of Carols, Oxford University Press, 1999, pv

[2] William J. Phillips, Carols, Their Origin, Music, and Connection with Mystery Plays, Forgotten Books, 2015, pi.

[3] Western Drama Through The Ages, A Student Reference Guide, Vol 1, edited by Kimball King, Greenwood Press, 2007, p85 https://books.google.ca/books?id=94LDaZ3efUYC&pg=PA85&lpg=PA85&dq=%22vernacular+drama%22&source=bl&ots=RJIUKJHytJ&sig=poA6kW1h6JdRCCWpEN47i7gq0Jw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwid7b-S-rLYAhXs6YMKHTIcAPA4ChDoAQgqMAE#v=onepage&q=%22vernacular%20drama%22&f=false

[4] Phillips, Carols, p24.

[5] Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/art/mystery-play, accessed January 6, 2018.

[6] http://www.historic-uk.com/CultureUK/Wassailing/

[7] History.org, http://www.history.org/foundation/journal/holiday06/wassail.cfm

[8] Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Oliver-Cromwell, accessed, December 31, 2017

[9] Dearmer, Oxford Book of Carols, p ix

[10] History.com, http://www.history.com/topics/industrial-revolution, accessed January 7, 2018.

[11] Mark Connelly, Christmas, A History, i=I.B. Tauris & Co., 1999, p62.

[12] Hymns and Carols of Christmas, https://www.hymnsandcarolsofchristmas.com/Hymns_and_Carols/Biographies/davies_gilbert.htm, accessed January 7, 2018.

[13] British Library, https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/christmas-carols-ancient-and-modern-by-william-sandys, accessed January 7, 2018

[14] Connelly, Christmas, p65

[15] Connelly, Christmas, p66.

[16] University of Rochester, https://urresearch.rochester.edu/institutionalPublicationPublicView.action?institutionalItemVersionId=26596. accessed January 1, 2018

[17] W.H. Monk, Hymns Ancient and Modern, J. Alfred Novello, 1861. Digitized version accessed, January 1, 2018, https://ia801701.us.archive.org/33/items/modeance00chur/modeance00chur.pdf

[18] Connelly, Christmas, p67

[19] Connelly, Christmas, p67

[20] Connelly, Christmas, p73

[21] Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed January 1, 2018. https://www.britannica.com/art/carol.

[22] Connelly, Christmas, p75.

[23] Connelly, Christmas, p87

[24] Trinity Church Boston, http://www.trinitychurchboston.org/about/history, accessed January 2, 2018.

[25] Andrew Gant, The Carols of Christmas, Nelson Books, 2015, p39.

[26] Gant, The Carols of Christmas, p39.

[27] Gant, The Carols of Christmas, p44

[28] Christian History, http://www.christianitytoday.com/history/people/poets/charles-wesley.html accessed, January 4, 2018,

[29] Gant, The Carols of Christmas, p107

[31] Gant, The Carols of Christmas, p111

[32] Gant, The Carols of Christmas, p113

[33] Gant, The Carols of Christmas, p113

[34] Silent Night Museum, https://www.salzburg.info/en/sights/excursions/stille-nacht-museum-oberndorf, accessed January 2, 2018.

[35] The Telegraph, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/topics/christmas/12062012/Silent-Night-A-short-history-of-Britains-favourite-Christmas-carol.html , accessed January 2, 2017

[36] Gant, The Carols of Christmas, p57

[37] Gant, The Carols of Christmas, p59

[38] Gant, The Carols of Christmas, p79

[39] Gant, The Carols of Christmas, p77

[41] Gant, The Carols of Christmas, p79

[42] Gant, The Carols of Christmas, p79

[43] The Canadian Encyclopedia, http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/reginald-fessenden/ accessed January 6, 2018

Bibliography

Mark Connelly, Christmas, A History, I.B. Tauris & Co., 1999 Percy Dearmer, R. Vaughan Williams, Martin Shaw, Oxford Book of Carols, Oxford University Press, 1999 Andrew Gant, The Carols of Christmas, Nelson Books, 2015

William J. Phillips, Carols, Their Origin, Music, and Connection with Mystery Plays, Forgotten Books, 2015

Links

Western Drama Through The Ages, A Student Reference Guide, Vol 1, edited by Kimball King, Greenwood Press, 2007, p85 https://books.google.ca/books?id=94LDaZ3efUYC&pg=PA85&lpg=PA85&dq=%22vernacular+drama%22&source=bl&ots=RJIUKJHytJ&sig=poA6kW1h6JdRCCWpEN47i7gq0Jw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwid7b-S-rLYAhXs6YMKHTIcAPA4ChDoAQgqMAE#v=onepage&q=%22vernacular%20drama%22&f=false

Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/art/mystery-play, accessed January 6, 2018.

Historic-UK.com, http://www.historic-uk.com/CultureUK/Wassailing/

History.org, http://www.history.org/foundation/journal/holiday06/wassail.cfm

Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Oliver-Cromwell, accessed, December 31, 2017

History.com, http://www.history.com/topics/industrial-revolution, accessed January 7, 2018.

Hymns and Carols of Christmas, https://www.hymnsandcarolsofchristmas.com/Hymns_and_Carols/Biographies/davies_gilbert.htm, accessed January 7, 2018.

Bitish Library, https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/christmas-carols-ancient-and-modern-by-william-sandys, accessed January 7, 2018

University of Rochester, https://urresearch.rochester.edu/institutionalPublicationPublicView.action?institutionalItemVersionId=26596. accessed January 1, 2018

Hymns Ancient and Modern, J. Alfred Novello, 1861. Digitized version accessed, January 1, 2018, https://ia801701.us.archive.org/33/items/modeance00chur/modeance00chur.pdf

Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed January 1, 2018. https://www.britannica.com/art/carol.

Trinity Church Boston, http://www.trinitychurchboston.org/about/history, accessed January 2, 2018.

Christian History, http://www.christianitytoday.com/history/people/poets/charles-wesley.html accessed, January 4, 2018,

Silent Night Museum, https://www.salzburg.info/en/sights/excursions/stille-nacht-museum-oberndorf, accessed January 2, 2018.

The Telegraph, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/topics/christmas/12062012/Silent-Night-A-short-history-of-Britains-favourite-Christmas-carol.html , accessed January 2, 2017

The Canadian Encyclopedia, http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/reginald-fessenden/ accessed January 6, 2018

Thank you so much. I appreciate learning the history behind these Christmas carols. I had no idea.

Thank you providing how Carols were orginated . Its History let us teach new generation

I a Buddhist by religion stil i respect all religions in this world